I have wanted to be in Normandy on 6 June for as long as I can remember. To stand on those beaches, to look World War II veterans in the eye and say: “Thank you for your service, Sir.” In 2024, for the 80th anniversary of D‑Day, that wish finally came true.

Why this anniversary mattered

The 80th anniversary at the Normandy American Cemetery was always going to be special: nearly 10,000 people gathered on the cliffs above Omaha Beach, with some of the last living World War II veterans seated in the front rows, surrounded by their families and world leaders. For many of them, it was probably the last time they would return together to the place that defined their youth and changed the course of history.

The Normandy American Cemetery is the resting place of more than 9,000 Americans who died during the D‑Day landings and the Battle of Normandy, each cross or Star of David aligned with almost impossible precision. Walking between those rows, with small American and French flags planted at the base of the graves, you understand that “freedom” is not an abstract word but a field of names and dates.

Getting there: a night flight and a race against roadblocks

My journey started with a night flight to Paris, followed by an early‑morning train to Bayeux, the small medieval town that becomes a logistics hub every June. I was not travelling alone, though: I had a Panasonic Lumix S5 II in my backpack, kindly offered by the team at Panasonic Romania, so that I could try to capture this once‑in‑a‑lifetime event in images as well as in words. On regular days, Bayeux is all half‑timbered houses, quiet canals, and slow cafés, but in the first week of June, it transforms into a living open‑air museum of 1944: military reenactors in olive drab uniforms, period jeeps rumbling through the streets, and flags from all Allied countries hanging from every window.

On 5 June, I picked up my media accreditation and discovered what “D‑Day traffic” really means. Roads towards the coast were intermittently closed by police and gendarmes as convoys of veterans and officials moved between ceremonies, and every roundabout seemed to hold at least one Sherman tank or restored truck waiting for a parade. In the afternoon, I joined a short tour with Bayeux Shuttle, driving out towards Pointe du Hoc and Omaha Beach to get a first sense of the terrain before the big day.

Omaha Beach: a quiet shoreline with a loud past

Nothing prepares you for how peaceful Omaha Beach looks on a sunny June afternoon. The sand is wide and golden, the tide comes in slowly, and on most days you see families walking their dogs, children playing near the water, and the occasional rider on horseback. During the 80th anniversary week, that quiet was punctuated by fly‑pasts of military aircraft and lines of restored vehicles parked along the shore, engines idling as visitors posed for photos.

Standing there with the wind from the Channel in my face, listening to the guide explain the sectors, the first waves, the chaos of the landings, it was impossible not to imagine the same sand covered in smoke and metal. I realised that the next morning I would be sitting above these very cliffs, watching some of the men who survived that day come back to say goodbye to their friends.

Dawn at the Normandy American Cemetery

On 6 June my alarm rang long before dawn. By 4:30 a.m. I was in a car leaving Bayeux, navigating a maze of checkpoints and diversions before the last roads towards Colleville‑sur‑Mer closed completely. Around 5:30 we reached a forested parking area and joined a growing line of people walking quietly towards the security perimeter: officers in dress uniforms, and journalists dragging camera gear in the half‑light.

The security was as strict as you would expect for an event that brought together dozens of heads of state and senior military leaders, but the facilities were surprisingly basic; there was a temporary media tent with long tables, power outlets and screens streaming the official feed, yet not even a stand where you could buy a cup of coffee. After checking my camera one last time and making sure my badge said “MEDIA” in bold letters, I walked out towards the press tribune, just as the rising sun lit up the huge stage built in front of the statue “The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.”

The ceremony: where protocol meets raw emotion

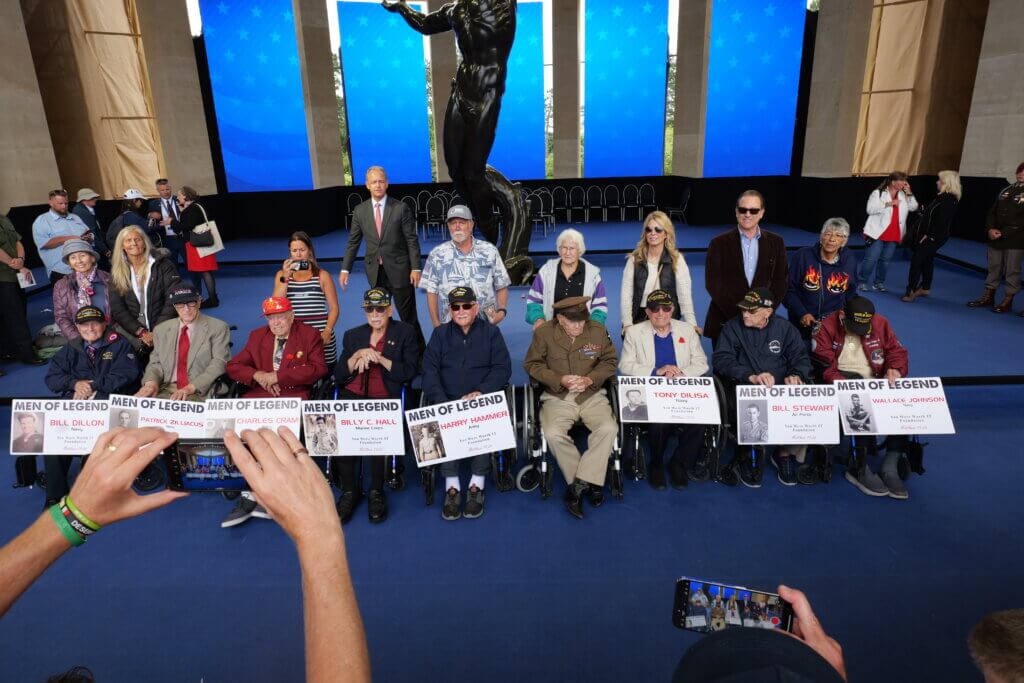

By 11:00 a.m., every seat along the red carpets was filled. Veterans sat in the front, wrapped in jackets against the wind, caps and medals telling the story their bodies no longer could. Behind them, families, active‑duty soldiers, and guests from many countries waited as national anthems were played, honor guards marched, and the formal program began.

The speeches were powerful, but what struck me most was when the cameras cut away from the lectern to show close‑ups of the veterans’ faces on the giant screens. Some wiped away tears, others stared straight ahead, lost somewhere between memory and the present, as leaders talked about democracy, alliances, and the price of freedom. The moment the fly‑past roared overhead, every head tilted towards the sky, and for a split second, the sound was probably not very different from what they had heard 80 years earlier.

Meeting Bob Pedigo: looking history in the eye

Among the veterans present in Normandy this year was Robert “Bob” Pedigo, a U.S. Army Air Corps nose gunner and bombardier who flew over France on D‑Day in a B‑24 Liberator nicknamed the “Silent Yokum.” As a young man from Indianapolis who had worked odd jobs during the Great Depression to help his family, he found himself on 6 June 1944 looking out from the nose of his aircraft at a sky and sea filled with thousands of Allied planes and ships all heading towards Normandy.

Eighty years later, Bob returned to those same shores as a 100‑year‑old veteran, travelling with other World War II servicemen on a specially organised honor flight that took them first to Paris and then to the ceremonies at Omaha Beach and the Normandy American Cemetery. When I met him, his handshake was still firm, and his eyes incredibly clear; saying “Thank you for your service, Sir” felt inadequate, but also the only honest thing to say to someone who had literally watched D‑Day unfold from the front of a bomber.

Knowing now that Bob passed away a few months later at the age of 101 makes that brief encounter even more precious: it was not just a selfie with a veteran, but a photograph with one of the last living witnesses of the day that changed Europe’s fate.

Between remembrance and festival

One of the most striking things about the D‑Day week in Normandy is how remembrance and festival coexist in the same fields and villages. In one direction, you see rows of perfectly maintained white crosses, stretching towards the horizon under a grey sky. A few kilometres away you find fields full of olive‑drab jeeps, food stalls, swing bands and vendors selling reproduction signs pointing to Bastogne, Nijmegen or “War Correspondents’ Office.”

At times, this contrast feels almost uncomfortable: children eating ice cream next to a World War II tank, or couples taking selfies in front of bunkers designed for killing. But watching veterans interact with these scenes, you understand that many of them see the living, noisy Normandy of today as proof that their sacrifices were not in vain. The fact that you can drink a coffee in Bayeux, walk safely on Omaha Beach and then attend a solemn ceremony in the cemetery is, in itself, part of the legacy they fought for.

Practical notes if you want to go

If you are thinking about attending a future D‑Day anniversary, especially a major one like the 85th, a bit of planning goes a long way. Tickets for the 6 June ceremony at the Normandy American Cemetery are free but allocated through a lottery, and information is usually published months in advance by the American Battle Monuments Commission and the U.S. Embassy in France. Accommodation near Bayeux and along the coast sells out quickly in milestone years, so booking many months ahead is almost mandatory.

Joining a local tour company such as Bayeux Shuttle can help you understand the historical context while also solving the problem of driving and parking on narrow country roads during one of the busiest weeks of the year. And if you manage to get a media accreditation, be prepared for very early mornings, long walks through security perimeters, and surprisingly spartan facilities – but also for a front‑row seat to living history.

Walking away from Normandy

When the ceremony ended and the crowds slowly dispersed, I stayed behind in the cemetery for a while, walking among the graves until the sound of buses and helicopters faded. Somewhere between the names and the dates, between the reenactors’ parades and the veterans’ wheelchairs, it became clear that D‑Day is not just a chapter in a textbook, but a responsibility that passes from one generation to the next.

Leaving Normandy that evening, with my camera full of images and my accreditation still hanging around my neck, one thought stayed with me: the world today is far from perfect, but it is at least more free because, on a cold June morning in 1944, thousands of very young people walked into the surf and did not turn back.

This trip was documented using a Panasonic Lumix S5 II loaned by Panasonic Romania; all impressions and opinions are entirely my own.